12 ANGRY MEN (1957)

Most of the jurors in a murder trial want to convict the defendant and go home... but a single hold-out tries to change their minds.

Most of the jurors in a murder trial want to convict the defendant and go home... but a single hold-out tries to change their minds.

A courtroom drama without a courtroom to speak of, 12 Angry Men became that way almost by accident. Reginald Rose’s 1954 television play was based in one room by necessity, since live TV couldn’t easily cope with set changes back then, and when Rose came to adapt it as director Sidney Lumet’s big-screen debut a few years later he simply decided to stick to the original format. Only a handful of unimportant scenes exist outside and inside the courthouse: one brief shot of the defendant in the courtroom itself, and a few minor episodes in a washroom stray beyond the jury room where the majority of the story takes place.

It’s 12 Angry Men’s focus that makes it work so well. Focus in both a metaphorical sense (although we learn a little about the characters as the film progresses, the jury’s debate is almost the whole of it), and in a literal one because Lumet and cinematographer Boris Kaufman famously designed their shots so that the film feels more and more hemmed-in as it goes on.

Rose had based his TV play on his own experience as a juror, but he linked it also to McCarthyism and the importance of speaking out against prejudice and persecution. For Lumet, himself coming from TV, it might’ve seemed an obvious choice for a big-screen directorial debut given his later career and its frequent critique of the criminal justice system and social issues in movies like The Pawnbroker (1964), Serpico (1973), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and The Verdict (1982), but in fact it was Henry Fonda who took the initiative.

Indeed, Fonda and Rose funded 12 Angry Men themselves after being unable to convince studios to back a movie without any female characters and just one rather dull set, and it was Rose who suggested Lumet. For the film, Rose was able to restore some material that had been deleted from his original TV screenplay, and although he also later adapted it for the stage in several versions (with notable differences from the movie, though they don’t change its overall thrust), it’s surely Lumet’s 1962 production that’s remained best known.

Set in New York City on the hottest day of the year, 12 Angry Men follows from beginning to end the deliberations of a jury in the trial of a young man—little more than a boy—accused of murdering his father. The audience never knows whether the defendant is guilty or innocent, and indeed a point reiterated by Rose’s script is that only doubt, rather than certainty of innocence, is needed for an acquittal.

The jury starts out 11-1 in favour of conviction but they’ve been instructed by the judge to reach a unanimous verdict, and so the bulk of the movie concentrates on their discussions and sometimes heated arguments. (Walter Bernstein, a screenwriter and friend of the director, said that Lumet “liked situations where actors could come at each other.”)

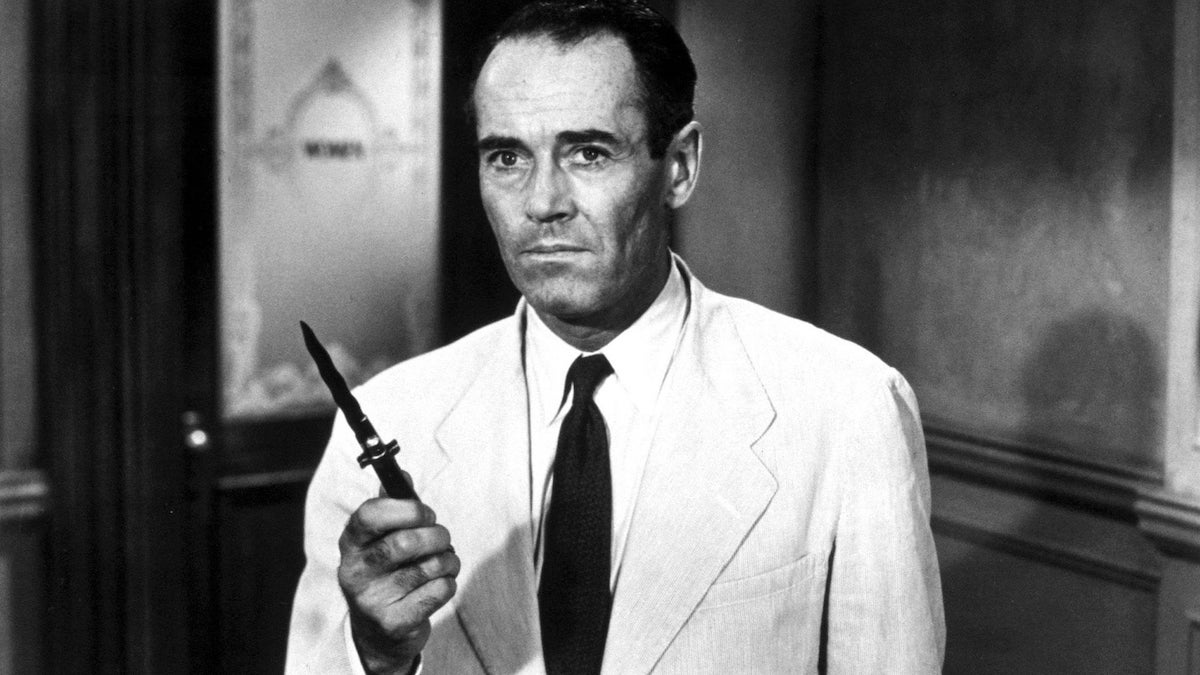

The “guilty” voters try to persuade the one hold-out, Davis (Fonda), to change his vote so they can all go home (and the defendant can go to his death), while Davis tries to convince others of his reasonable doubt. This to-and-fro is repeatedly paused for votes, and inevitably minds are changed over the course of the film, but a unanimous decision seems elusive…

12 Angry Men is, then, almost entirely a film of talking, although Lumet and Rose do a great deal to vary it with as much physical action as is possible within its constraints. Characters get up, walk around, wipe their face, take their jacket off, fiddle with a fan, produce an unexpected item from a pocket, pace out a distance, examine a drawing… often there are several people moving simultaneously, and changes in the weather also help to prevent monotony.

This makes the individuality of the characters, and the differences between their positions, the keys to the film. And every one of the 12 jurors—all of them men, as was the norm (although not the legal requirement) in NYC at the time—is distinctive, with their backgrounds informing their speech and action convincingly.

Perhaps the first to stand out is ‘Juror 7’ (Jack Warden), a baseball fan anxious to reach a decision so he can get to a big game; his lack of interest in the case is obvious from the beginning, and even much later in the film he can’t be bothered to leave the table in protest against the racist tirade of ‘Juror 10’ (Ed Begley) when most of his fellow jurors do.

A complete contrast is provided by ‘Juror 1’ (Martin Balsam), jury foreman and high school football coach; an open and amiable man, seeming a bit ineffectual at first yet gaining strength later. So, indeed, do many of the other jurors who initially appear mild to a fault but increasingly stand their ground. Among them are ‘Juror 2’ (John Fiedler), a balding, bespectacled bank clerk, and elderly McCardle (Joseph Sweeney giving one of the best performances).

Utterly different in character is ‘Juror 3’ (the slightly OTT Lee J. Cobb), a small businessman, easily angered, and adamant about the defendant’s guilt and seeming almost personally motivated to convict him. Others who the audience will not warm to so easily include ‘Juror 4’ (E.G. Marshall), upright and a little priggish, unemotional behind his pursed lips, and ‘Juror 12’ (Robert Webber), an advertising executive who evokes an insecure, boastful version of Mad Men’s Don Draper.

And then, of course, there’s Fonda’s Davis, almost saintly with his white suit, his easy manner and his sense of civic responsibility. Still, if this is a little overdone, it needs to be acknowledged that none of the jurors in 12 Angry Men are intended to be entirely realistic: they all represent certain types.

It’s no secret which of these types Rose and Lumet themselves side with and against. Fonda’s Davis is almost a hero, Cobb’s Juror 3 verges on a villain for a large part of the runtime. And it’s notable that those who align themselves first with Fonda are the obvious immigrant, the man from a poor background, and the very old man (i.e. the marginalised). Lumet, a rather nerdish boy who had later experienced bullying in the army, clearly enjoys depicting the meek inheriting the jury room if not the Earth.

Still, if 12 Angry Men isn’t exactly subtle neither as is generally overstated, one Fonda speech being the exception. And Rose’s writing is skilful, as evidence is communicated well to the audience (and sometimes comes as surprisingly as it might be in a “real” courtroom drama), essential revelations are inserted smoothly, and although the dialogue isn’t quite realistic it has a natural flow.

As important as the writing is the directorial and photographic style. Lumet’s approach is in some ways realist—he mostly chose local New York actors rather than famous Hollywood faces, he asked the performers to wear their own clothes, and the musical score by Kenyon Hopkins (for modest chamber forces) is absent for most of the film.

However, visually Lumet and Kaufman devised a stylised plan for 12 Angry Men, described as a “lens plot” by the director. “As the picture unfolded, I wanted the room to seem smaller and smaller. That meant that I would slowly shift to longer lenses as the picture continued… In addition, I shot the first third of the movie above eye level, and then, by lowering the camera, shot the second third at eye level, and the last third from below eye level.” Similarly, there are three distinct phases of lighting: bright daylight at the beginning, then the darkness of an outside storm, and then brightness again as the interior lights are switched on.

Although not without its critics (the idea of the “lens plot” was termed “portentous” by David Bordwell), this and the writing serve to ratchet up the mood effectively, and a film which feels quite low-key at is opening concludes in high drama without the audience ever noticing a specific transition point.

12 Angry Men is small scale in most senses, but not thematically. The first shot, an awestruck camera ascending columns outside the courthouse to reveal its carved proclamation—‘The Administration of Justice is the Firmest Pillar of Good’—makes one of Rose’s and Lumet’s principal concerns obvious. (Inside, a much less impressive sign saying SHELTER is also an evocative indication of the era.)

But the film is interesting and unusual in that it’s more anxious about the process of justice than the outcome. While “not guilty” is clearly presented as the better choice, there’s no demonisation of “guilty” votes as such. For example, at one point the foreman’s on the “guilty” side but is still being presented as a reasonable man, helping Fonda’s Davis close a recalcitrant window and chatting with him. At another point, Juror 11 (George Voskovec) criticises Warden’s Juror 7 for changing to “not guilty” simply for convenience, without really believing it.

And the gradual exposures of prejudice—“they let those kids run wild up there”, a juror says of the Latino community; “he don’t even speak good English” is spoken with unconscious irony—would be more striking in 1957 than they are now. As Lumet’s biographer Maura Spiegel wrote, “by current standards, a weakness of the film is its reliance on the pathos of racial victimization. But in its time, the exposure of behind-closed-doors racism was medicinal and rare in a mainstream film.”

It’s true that the diehard “guilty” voters aren’t given strong arguments by the script and that, as Pauline Kael said, Fonda represents “the educated audience” with the defendant being “their dream of a victim”. David Thomson, too, makes the fair point that the film might be complacent in suggesting that the system ultimately does work. But then 12 Angry Men is not trying to be even-handed. It’s frankly passionate. But it’s passionate about being even-handed.

Well-received critically at the time, it earned three Academy Award nominations (for ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Director’, and ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, losing out to The Bridge on the River Kwai in all three cases), and made the Cahiers du Cinéma list of films of the year. It performed poorly at the box office, however, perhaps partly thanks to over-melodramatic marketing, but has since become firmly established as a classic.

There have been several international adaptations, William Friedkin directed a TV remake in 1997 (inspired by the O.J Simpson case), and of course the stage version gives 12 Angry Men repeated new leases of life. And it’s also been influential beyond the bounds of cinema, being described by Thane Rosenbaum as “a time capsule of American justice before the civil rights era and the expansion of civil liberties in the 1960s”, the film is widely used in education, from high school civics classes to corporate leadership training.

But the undoubted didacticism present in Lumet’s and Rose’s version never overshadows the intense, gripping narrative—and it remains one of the finest courtroom dramas ever made, notwithstanding the absence of a courtroom.

USA | 1957 | 96 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Sidney Lumet.

writers: Reginald Rose (based on his TV play).

starring: Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, Ed Begley, E.G. Marshall, Jack Warden, Martin Balsam & Jack Klugman.