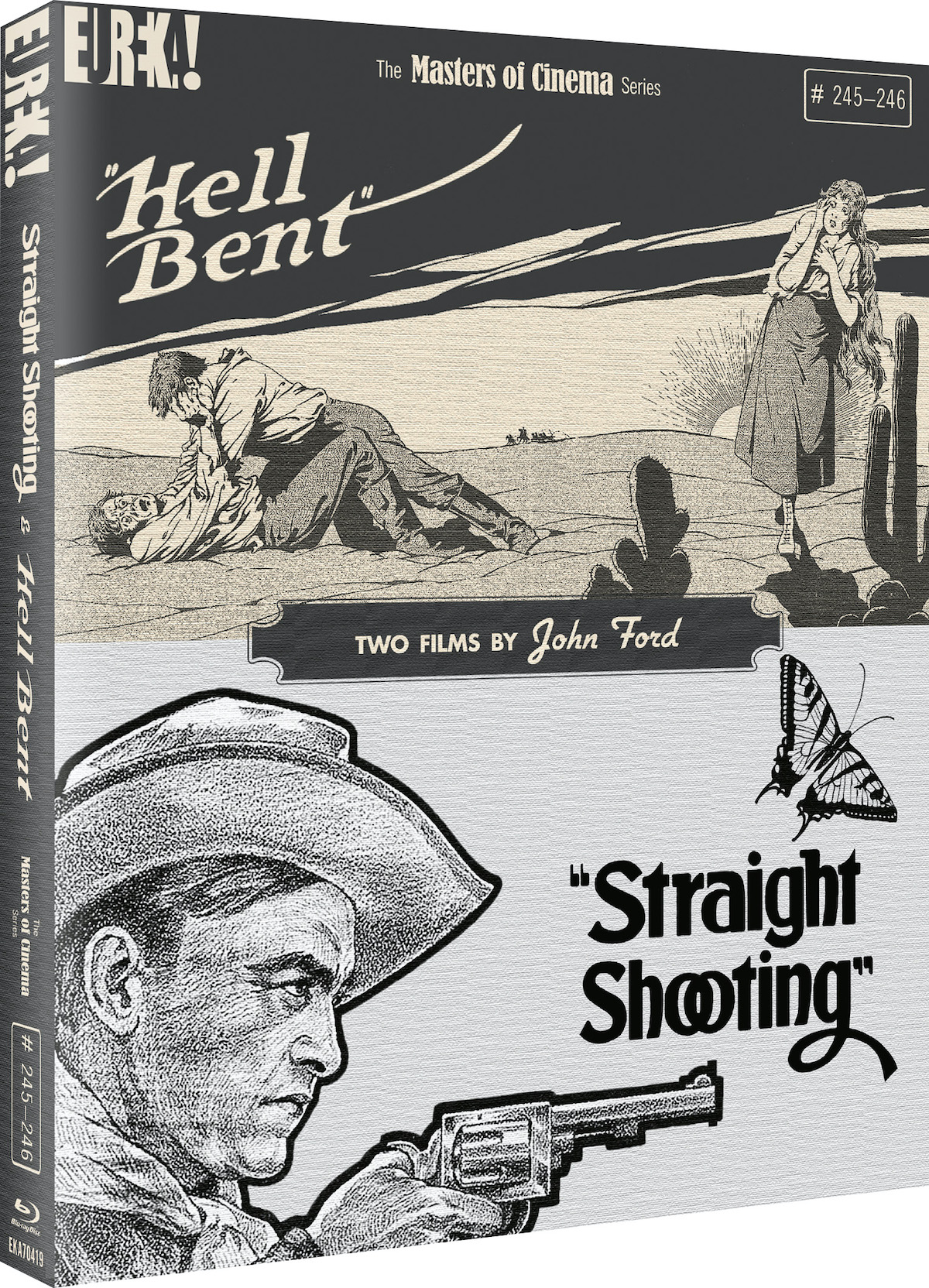

STRAIGHT SHOOTING (1917) • HELL BENT (1918)

Restored versions of two silent John Ford westerns star Harry Carey as the morally ambiguous Cheyenne Harry.

Restored versions of two silent John Ford westerns star Harry Carey as the morally ambiguous Cheyenne Harry.

Despite a long career that spanned many genres, John Ford is best known today for directing a string of famous Hollywood westerns, from Stagecoach (1939) to The Searchers (1956). But his career began much earlier, in the silent era, after he followed his actor-director brother Francis into the movies; and with the latest release in their ‘Masters of Cinema’ series, Eureka Entertainment bring well-deserved attention to Ford’s debut feature, Straight Shooting, as well as the related Hell Bent, with the same star in the same role.

The star in question is Harry Carey, who plays (and was instrumental in creating) Cheyenne Harry, an unusually ambiguous character for an early western. When we meet him in Straight Shooting he seems dissolute, an amoral baddie, a gun for hire, but it soon becomes apparent he does have principles (despite wearing a black hat), and will switch sides when required. Early shots of him in both films, appearing unexpectedly from a tree or reflected in water, underline that he’s not straightforward.

Carey, like Ford, would go on to have a career in ‘the talkies’, with his final films including Frank Capra’s Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939), King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946), and Howard Hawks’s Red River (1948)—but Cheyenne Harry remains his most significant legacy, and to a large extent these are Carey’s films as much as they are Ford’s. After all, the director acknowledged the movies he made with Carey—26 in total—“weren’t shoot-’em-ups, they were character stories.”

Straight Shooting was Ford’s first five-reeler and sets up, from the opening titles, the familiar conflict between cattlemen anxious to keep the land open for their herds and homesteaders trying to fence it in for cultivation. (Unsurprisingly, there’s no mention of Native Americans.)

The film is firmly on the homesteaders’ side, as one might guess from the names of the two groups’ leaders: the rough-sounding Thunder Flint (Duke Lee, with the air of Deadwood’s evil Cy Tolliver about him) aggressively fighting for the cattlemen’s cause, and the much gentler Sweet Water Sims (George Berrell) defending the homesteaders.

Still, Carey’s Cheyenne Harry is by far the most interesting character, not only in the way he transitions from apparent villain to near-hero, but also in the way the uncertainty is never quite resolved. Right at the end of the story, indeed, Harry’s dilemma—stay with Sweet Water and his daughter, or head out to the open range again?—strongly foreshadows John Wayne’s in The Searchers.

Similarly interesting, if lower-key, ambiguity is provided by the boy Danny, who works for Flint but like Carey has moral standards (and an interest in the girl too). He’s played Hoot Gibson, who also became a major cowboy star and was a frequent collaborator of Ford’s. By comparison we don’t see too much of Sweet Water and his daughter (Molly Malone); although the usual obeisance to audiences’ sentimental demands is paid, they’re a bit too saintly to be really interesting.

Besides the storyline, which is genuinely engaging, and the character of Cheyenne Harry, Ford’s directorial technique is what provides most of the continuing fascination with Straight Shooting. His composition is consistently terrific, and his sense of timing spot-on, both in the rapid-fire cross-cutting as the climactic gunfight approaches and in some quieter scenes earlier on. He uses iris effects for emphasis, but not too many of them, and there’s a sophisticated mix of shot types—including a striking extreme close-up of bad guy Fremont (Vester Pegg). Straight Shooting is an entertaining movie in its own right, and historically important both in Ford’s career and as an example of Carey’s character; most of all, though, it’s a choice example of a cinematic master in gestation.

US | 1917 | 62 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE | SILENT

Dramatically, Hell Bent is less gripping, less intense, and more romantic than Straight Shooting—much of it concerning the efforts of Carey’s Cheyenne Harry to rescue Bess (Neva Gerber) from the clutches of the wicked Beau (Joe Harris). It’s also more comic. For example, with a horse eating straw from the mattress of Cimmaron Bill (Duke R. Lee) and with a few nudge-nudge sniggering about tough guys sharing beds.

But it’s equally interesting as filmmaking, right from the highly unusual opening, where we see a novelist reading a letter from his publisher asking for more morally complex characters. The camera then moves to a Frederic Remington painting depicting the aftermath of a bar fight, and that painting comes alive as the first shot of the film proper. Ford and Carey aren’t only providing the complexity that the imaginary publisher’s imaginary public is demanding; they’re also overtly advertising that they are providing it.

There are many stylistic similarities between the two movies—not only in camera technique but also in the frequent emphasis on water and horses to give a believable physicality to the story and assure us it’s not just a bunch of actors on a set. (Thus we get plenty of horses in the rain, horses in rivers, and so on.) The notable difference, however, is that while there are occasional grand landscapes in Straight Shooting, giving a taste of the epic-scale Ford movies to come, there are many more of them in Hell Bent, culminating in an excellent desert montage leading to a long climactic sequence.

Carey, meanwhile, fills out his Cheyenne Harry character further with some nice touches. For example, he doesn’t know how to hold a teacup, so he warily imitates a properly-brought-up young lady. Hell Bent on its own is a less compelling film than Straight Shooting, but as a partner on a double bill it works perfectly, allowing us to see how Ford’s direction and Carey’s performances flourished together.

US | 1918 | 53 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE | SILENT

director: John Ford (as Jack Ford).

writers: George Hively (Straight) • John Ford (as Jack Ford), Harry Carey & Eugene B. Lewis (Hell).

starring: Harry Carey, Duke R. Lee & George Berrell (Straight) • Harry Carey, Duke R. Lee & Neva Gerber (Hell).