THE SOCIAL NETWORK (2010)

A student creates the social networking site that would become known as Facebook, but is sued by the twins who claimed he stole their idea and the co-founder squeezed out of the business.

A student creates the social networking site that would become known as Facebook, but is sued by the twins who claimed he stole their idea and the co-founder squeezed out of the business.

During the production of The Social Network in early 2010, Facebook celebrated its sixth anniversary. In just six short years, the platform had gone from a dorm room experiment to enough of a phenomenon that a major motion picture based on its troubled origins was in development. The film, affectionately referred to as “the Facebook movie” by pop culture at the time, turns fifteen this month. While it was already a mainstream staple then, today its impact on global culture can’t be overstated.

The idea of a Facebook movie drew scepticism from many at the time. One could only imagine the different directions a wayward studio might take such a film. It could have been a novelty, a satire, or a cheap cash grab capitalising on an already massive IP. But when it arrived in cinemas touting names like David Fincher (Panic Room) and Aaron Sorkin (The West Wing), those low expectations quickly dissolved. Both already had well-regarded filmographies, and critics immediately added The Social Network to their best work. Both received Academy Award nominations, with Sorkin winning for ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’. The film earned eight nominations in total, including ‘Best Picture’. What had looked like an internet gimmick became an instant classic.

Fifteen years later, it’s striking how little of The Social Network feels dated. The clothes, the laptops, the flip phones, and the Facebook layout itself are noticeable relics. But the anxieties at its core—the struggle for power, the isolation, the desire to be the best—are timeless and perhaps even more relevant today than ever. The film also predicted aspects of ugly internet behaviour that weren’t as prevalent then but have since become depressingly common.

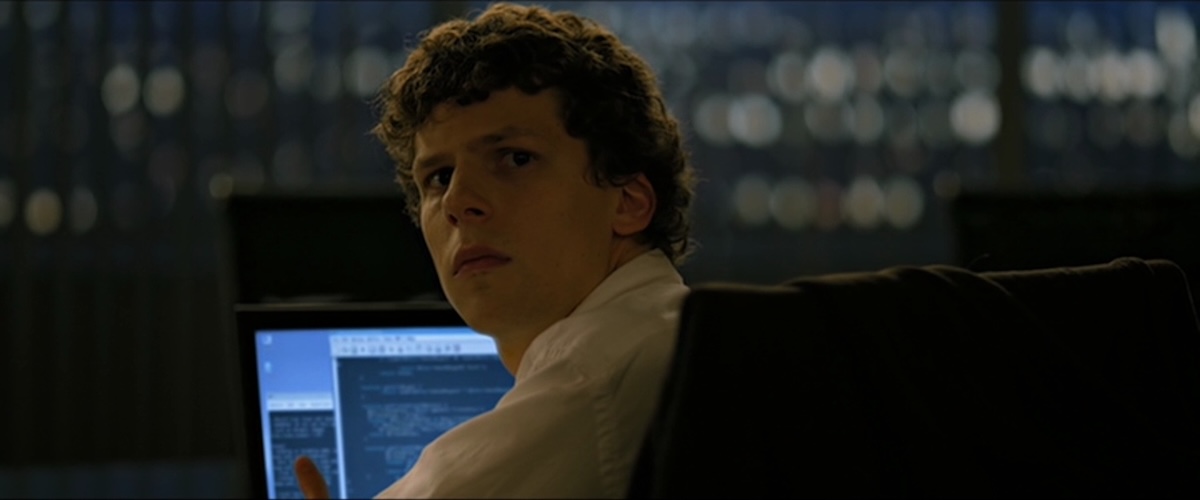

David Fincher is a director known for razor-sharp precision and obsessive attention to detail, and it’s fascinating to see how many subtle touches run throughout the film that aren’t obvious on a first viewing. There’s no better example than the very first scene. A slow fade from black drops the audience into a conversation between the now-infamous Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg, who earned a ‘Best Actor’ Oscar nomination for his portrayal) and Erica Albright (Rooney Mara). It’s not only a perfect character set-up but also a blueprint for how the story will be told. The conversation is one-sided until it becomes confrontational. We get a peek at the quippiness that will come to define Zuckerberg, but the scene also plays like a deposition. A favourite piece of trivia is that it reportedly took these two actors 99 takes to achieve what Fincher considered authentic—a conversation at a clipped pace, with all the right awkwardness and pretension to prepare the audience for what lies ahead.

Zuckerberg is quickly established as not a particularly good person. No sooner has he returned to his dorm after being dumped than he is cruelly roasting Erica on his online journal. That frustration leads directly into his creation of Facemash, a site that allows users to choose which female student is more attractive using hacked photos from Harvard sororities. It’s quite the ironic origin story for a platform that would come to dominate global social life.

It’s worth remembering that The Social Network never claimed to be a true story. It is largely a work of fiction inspired by real events. Sorkin, who admitted he wasn’t a Facebook user and knew very little about the platform, takes considerable liberties to fit the narrative. That opening scene, for example, meticulously crafted and performed, involves one of the only appearances by Erica Albright. She remains an important symbolic presence in Zuckerberg’s backstory, but she does not exist in real life. Still, Sorkin’s story has become widely accepted as fact, cementing itself in the public imagination.

Facemash also introduces Zuckerberg’s roommate and closest friend, Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield). “Wardo” provides the crucial algorithm but questions Zuckerberg’s motives and warns repeatedly that it’s a bad move. This early dynamic—Zuckerberg’s drive clashing with Eduardo’s caution—continues throughout their relationship. More importantly, Facemash leads straight into the first deposition scene between Zuckerberg and his lawyers, and Eduardo and his. The depositions become the framework through which the rest of the story unfolds.

This first deposition also briefly introduces Marylin Delpy (Rashida Jones), a junior lawyer at Zuckerberg’s firm. Her role is small but significant. She is an objective observer, not unlike the audience itself. As much as Fincher underlines Zuckerberg’s questionable morality in the opening acts, the film still resists an easy answer to whether he is the hero or the villain of Facebook’s story. Over the course of the film, Delpy wrestles with that very question and delivers her verdict in the final line: “You’re not an asshole, Mark. You’re just trying so hard to be.”

A major theme Fincher weaves into the film is the performance of self. One of Facebook’s most enticing features is that each user decides how they are seen. A person can project their true self, a slightly exaggerated version, or something entirely false. The Social Network mirrors this: a story about the performances we stage in real life. The depositions serve as the ultimate stage, where every character shapes their narrative to look like the hero. Beyond that, every major figure wears a mask of some kind. Zuckerberg is a brilliant coder but socially clumsy, projecting control through his empire while his personal life is lonely and chaotic. Eduardo wants to be the loyal friend but also seeks validation as Facebook’s CFO.

Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (both played in a dual role by Armie Hammer) embody this theme most clearly. Introduced during a rowing sequence, they outpace rivals with effortless grace, their privilege on full display. After learning of Facemash, they approach Zuckerberg with an idea that plants the seed for Facebook. Moments later, the film cuts to another deposition, this time with the twins suing Zuckerberg. They are the human embodiment of entitlement, yet they cast themselves as wronged underdogs. They project victimhood, but the audience must decide how much of it rings true.

The final piece of the Facebook puzzle as told in The Social Network is Sean Parker. Napster—the early-2000s software Parker co-founded—allowed users to share music freely and was eventually shut down, but not before permanently changing the music industry. The irony of casting Justin Timberlake, one of the pop stars most harmed by Napster, is delicious. Parker is magnetic, brash, and thrives as the centre of attention. It’s no surprise Zuckerberg gravitates towards him as Eduardo’s eventual replacement, both in business and in his life.

Casting Timberlake was a gamble. His limited acting background was met with scepticism, but he embodies Parker so completely that it’s hard to tell where performance ends and persona begins. Hammer’s dual role was also a risk, though more technical than dramatic. Initially, two actors were meant to play the twins, but Hammer’s performance was so convincing that the production entrusted the rest to VFX—an effect that still holds up in 2025. Yet the undeniable star is Jesse Eisenberg. His Zuckerberg is calculating, awkward, and relentless. His clipped delivery and icy tone transform what might have been a caricature into something disturbingly believable.

Even so, it could be argued that the film’s biggest champion is its editing by Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall. So much of The Social Network depends on pacing. With its structure intercutting depositions and flashbacks, the editing had to be seamless. It is. The rhythm is relentless, tension builds in boardrooms as though they were battlefields, and Sorkin’s dialogue lands like gunfire. In other films, depositions are dry. Here, they nearly toss the audience around.

Jeff Cronenweth’s cinematography is another essential element. With Fincher’s characteristic muted, wintry palette, Cronenweth captures the coldness at the heart of the story. Harvard looks romantic and historic, while the later scenes feel increasingly stark and sterile, mirroring Zuckerberg’s trajectory.

Then there’s the score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, groundbreaking in 2010 and still iconic. Often it hums beneath the surface; in other moments, it surges forward and dictates the mood. The six-note main theme, played over a low, menacing bass, perfectly encapsulates the duality of innocence and threat. It fits seamlessly with what unfolds on screen.

The themes of The Social Network feel almost prophetic. Zuckerberg’s rise mirrored the broader story of Silicon Valley: innovation fuelled by ambition, with ethics and friendship left behind. Today, as tech billionaires shape politics, culture, and even space travel, the film feels less like a drama about Harvard students and more like the origin story of our era.

The Social Network begins with a break-up and ends with a desperate refresh of a friend request. In between, it charts the birth of a digital empire built on obsession, betrayal, and loss. 15 years on, it still feels electric, urgent, and chillingly prescient.

Zuckerberg settled the lawsuits and called them victories. He built the empire and changed the world. But in Fincher’s telling, he also lost something deeper. He lost connection, he lost friendship, and in the end, he lost himself.

USA | 2010 | 120 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: David Fincher.

writer: Aaron Sorkin (based on the book ‘The Accidental Billionaires’ by Ben Mezrich).

starring: Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, Justin Timberlake, Armie Hammer, Max Minghella, Brenda Song, Rashida Jones, John Getz, David Selby, Douglas Urbanski, Rooney Mara, Joseph Mazzello & Dakota Johnson.