SARABAND FOR DEAD LOVERS (1948)

Forced into a joyless marriage with the future King George I of Great Britain, Sophia Dorothea falls in love with another man.

Forced into a joyless marriage with the future King George I of Great Britain, Sophia Dorothea falls in love with another man.

Helen Simpson’s 1935 novel Saraband for Dead Lovers might seem an odd choice of source material for a British film conceived just after the end of World War II. Its backdrop, the ambition of the 17th-century Hanoverian court to establish its Electoral Prince George Louis as King of Great Britain and Ireland, can be seen as a scheme for a German takeover of the British throne, or for a German-British alliance. But perhaps the contrast between the reality of Anglo-German relations in 1948 and the world of Basil Dearden’s film only heightened its credentials as a serious historical drama, which was how Ealing Studios sought to position its first colour feature.

Encouraged by its owner the Rank Organisation to start filming in colour to make its movies more attractive to overseas markets, Ealing decided with Saraband for Dead Lovers to depart from its usual more modest style and produce a lavish historical romance that would directly challenge Gainsborough Pictures, the specialist in such films. It even hired Stewart Granger, a leading man associated with Gainsborough, for the principal male role.

But Ealing also wanted a more serious and realist approach to the genre than Gainsborough’s melodramas offered, and the result ran the risk of becoming a compromise that pleased neither those who sought exciting fluff nor those who preferred grim realism. Indeed, Saraband for Dead Lovers (known in the US simply as Saraband) was an expensive flop.

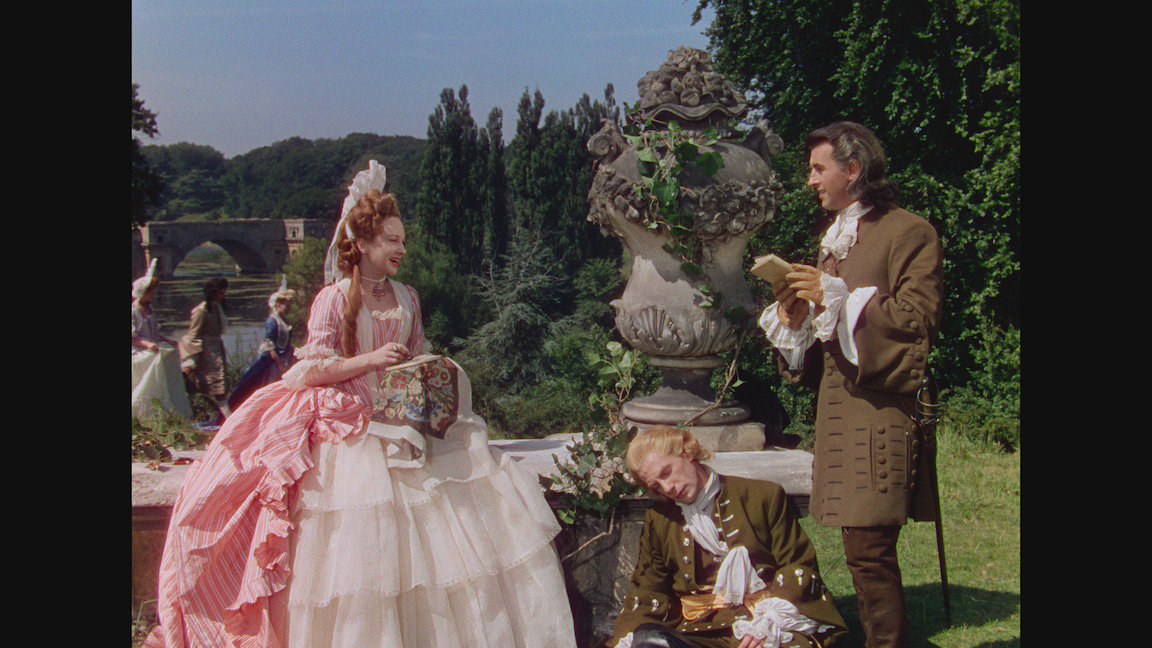

Certainly, it’s not without problems. Many contemporary critics thought it over-emphasised its visuals at the expense of developing characters properly, and the dense politics of the bewigged 17th-century German nobility can also be a little difficult to follow, especially at the beginning of the film. But there’s no denying it looks impressive, and a handful of strong performances—notably Flora Robson’s—go quite a long way toward making up for flatness in characterisation and a pace that can feel a bit too stately.

Simpson, who’d worked with Alfred Hitchcock, might have been the obvious choice for adapting her own novel in the 1930s, but by the time Ealing started to develop the film she had passed away, so John Dighton and Alexander Mackendrick delivered the screenplay. Both it and the novel draw on the true historical story of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (1666-1726), her marriage to George Louis, the Electoral Prince of Hanover who became Britain’s George I, and her affair with the Swedish Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck, who later disappeared and is presumed to have been murdered on George Louis’s orders. Opening and concluding with Sophia Dorothea (Joan Greenwood) writing a deathbed letter to her son, it’s told almost entirely in flashback with some voiceover.

Young Sophia Dorothea is an unwilling bride for George Louis, a notorious womaniser. “All the world knows what he is, how he lives,” says her mother (Mercia Swinburne) and a thunderstorm during the wedding seems to confirm both mother and daughter’s worst fears.

Moving from Celle to Hanover, Sophia Dorothea finds George Louis (a magnificently piggish, smirking Peter Bull) to be a boorish and unpleasant husband, and she soon falls in love with another outsider, the visiting Königsmarck (Granger, his name spelt Konigsmark in the movie). We first meet him playing high-stakes cards with George Louis and losing money he can’t afford—although, in a departure from Simpson’s novel, his poverty is no longer blamed on Jewish money-lenders. That might have been acceptable before the war, but not after the revelation of the Holocaust.

The affair is doomed, of course. Even though their marriage is loveless and they are estranged from the beginning, Sophia Dorothea is effectively a prisoner of George Louis and his family; a pawn in the political machinations of the German states, valuable as the mother of his heir, and financially useful too as the bringer of a handsome dowry. Meanwhile, Königsmarck’s situation is further complicated when the older Countess Platen (Robson) also falls for him, while in the background the Germans are fighting the Ottoman Empire in the Great Turkish War, and many of the male characters participate in the conflict.

There’s a lot of complex incident and historical detail in the narrative—much of it essential to explain just why Sophia Dorothea had to marry the awful George Louis—and it does become a burden on the film, running the risk of stifling the drama just as the Hanoverian court suffocates Sophia Dorothea. But this is at least partly compensated for by the colour visuals from Dearden and director of photography Douglas Slocombe, especially the vivid costumes and the exteriors (many of them shot in Prague, so much of Germany having been ruined in the war, these are generally more successful than the rather obvious sets used for interiors).

Slocombe went against the prevailing wisdom by lighting Saraband for Dead Lovers in a mannered, high-contrast way—the norm for black-and-white, but not at the time advised for colour—and the effect can be powerful. He said what mattered wasn’t “whether the hues are true to life but whether pleasing and dramatic use has been made of them”. Adding to this, Dearden occasionally stages scenes to resemble 17th-century paintings, a touch (later used with great panache by Kubrick in Barry Lyndon) that reinforces the historical atmosphere.

Most striking, however, is a single sequence in the middle of the film—the carnival led by the Lord of Misrule at the Hanover Fair—which with its cavorting, leering, masked faces and lack of dialogue recalls the extraordinary expressionist conclusion to Alberto Cavalcanti’s final story in Ealing’s recent Dead of Night (1945). As with a much briefer shot of a gargoyle spouting water right at the camera, the sheer unconstrained energy of this sequence brings into focus the passion, and violence, of emotions buried beneath the slow, formal, rule-bound behaviour of the court.

The score by Alan Rawsthorne is well-crafted throughout, but especially strong in this section as well as in a brief, tortured passage marking the return of a defeated army. Unlike in the US, where emigrés from Germany and Austria rather dominated the film-music scene, in Britain the use of home-grown classical composers such as Britten, Walton, and Vaughan Williams was a real strength of the country’s cinema, and Rawsthorne’s music for Saraband for Dead Lovers is a fine example, mostly written in an approachable contemporary idiom that is dramatic without becoming melodramatic. Only at one point is quasi-Baroque pastiche noticeable.

Not all of the performances stand the test of time; it’s very much of its period, especially in some distinctly unreal deaths, and Greenwood and Granger as the romantic leads frequently do little beyond looking unhappy and sensitively heroic, respectively. But Robson, in an atypically vulnerable role as the older woman whose love for Königsmarck is unrequited, is believable and moving. Her surprising and savage assault on him at the very end provides the film’s most startling single moment.

Françoise Rosay also stands out as George Louis’s mother, another woman who understands the rules of power games, while Bull (although misleadingly nearly 15 years older than the very young George Louis at the time of his marriage) is deliciously nasty. Anthony Quayle appears in one of his first film roles, while Anthony Steel, later to be a star of British war and adventure films, makes his uncredited debut.

Its period setting and intermittent soldiering notwithstanding, Saraband for Dead Lovers is far from a swashbuckler (the climactic swordfight feels rather obligatory) but nor is it really much of a romance; we get little sense of the relationship between Sophia Dorothea and Königsmarck, and the overall mood is much more one of isolation, oppression and futility than of blossoming love.

To that extent, though, it does succeed in conveying the reality of Sophia Dorothea’s marriage and the unlikelihood of a happy ending for her and Königsmarck. And though it can seem to plod at times, at others it comes alive—through Robson’s performance, for example, Rawsthorne’s music, the nearly surreal fair sequence, and of course the glorious Technicolor.

UK | 1948 | 96 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Basil Dearden.

writers: John Dighton & Alexander Mackendrick (based on the novel by Helen Simpson).

starring: Stewart Granger, Joan Greenwood, Flora Robson & Peter Bull.