NAUSICAÄ OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND (1984)

Warrior and pacifist Princess Nausicaä desperately struggles to prevent two warring nations from destroying themselves and their dying planet.

Warrior and pacifist Princess Nausicaä desperately struggles to prevent two warring nations from destroying themselves and their dying planet.

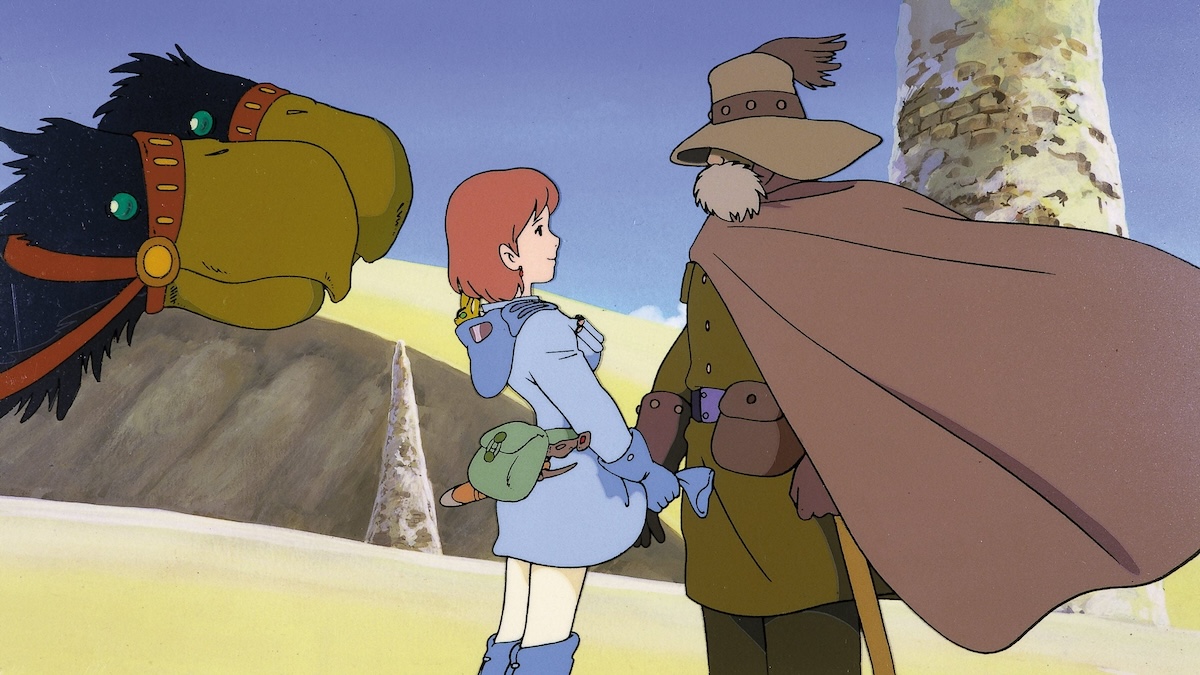

A cloaked figure trudges through the dusty, arid landscape. Ruins lie around them, remnants of a world that has utterly deteriorated, a civilisation that disintegrated due to human myopia. Pulling their cloak tighter, they turn away from the ruins and plod on, leading their pack animal behind them. “Let’s go,” they mutter. “Soon this place too will be consumed by the toxic jungle.”

This is the world humans must now inhabit: a post-apocalyptic wasteland, devoid of vegetation except for the ever-encroaching toxic jungle. This environment suffocates and throttles life by emitting noxious gases and poisonous spores. Few cities still prevail, causing both existential dread and debilitating factionalism. Instead of tackling the environmental fallout mankind created, nations have turned on each other in a desperate attempt to ensure their survival. Amid this conflict, only Nausicaä, Princess of the Valley of the Wind, offers any hope of uniting humanity and saving the world.

How can anyone dislike Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind / 風の谷のナウシカ? This sublime, spellbinding fairy tale for modern times seamlessly weaves together themes of animism and environmentalism within a science-fiction epic. Here, the magic on display is the majesty of the natural world and the power of human empathy. Featuring incredible story structure, superb pacing, and complex characters, Nausicaä explores universal themes that are becoming increasingly important to consider. This marks writer and director Hayao Miyazaki’s first masterpiece, a work entirely devoid of flaws.

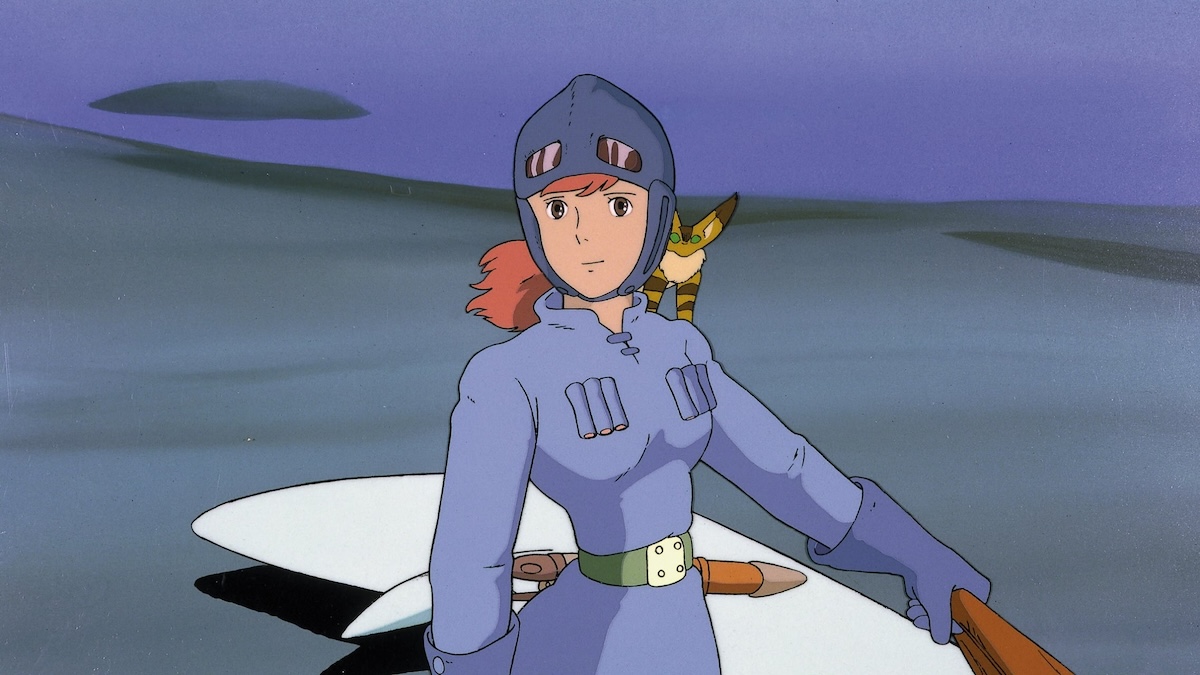

Perhaps the first thing that struck me upon rewatching this classic anime was the exceptional world-building on display. One of Miyazaki’s greatest strengths has always been his ability to create elaborate and surreal environments while simultaneously developing characters. In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the universe Miyazaki creates is arguably the most vivid and layered of his entire career. Every detail about this alternative reality connects to another, demonstrating that nothing is included simply for the sake of being fantastical; instead, everything is purposeful and well thought out.

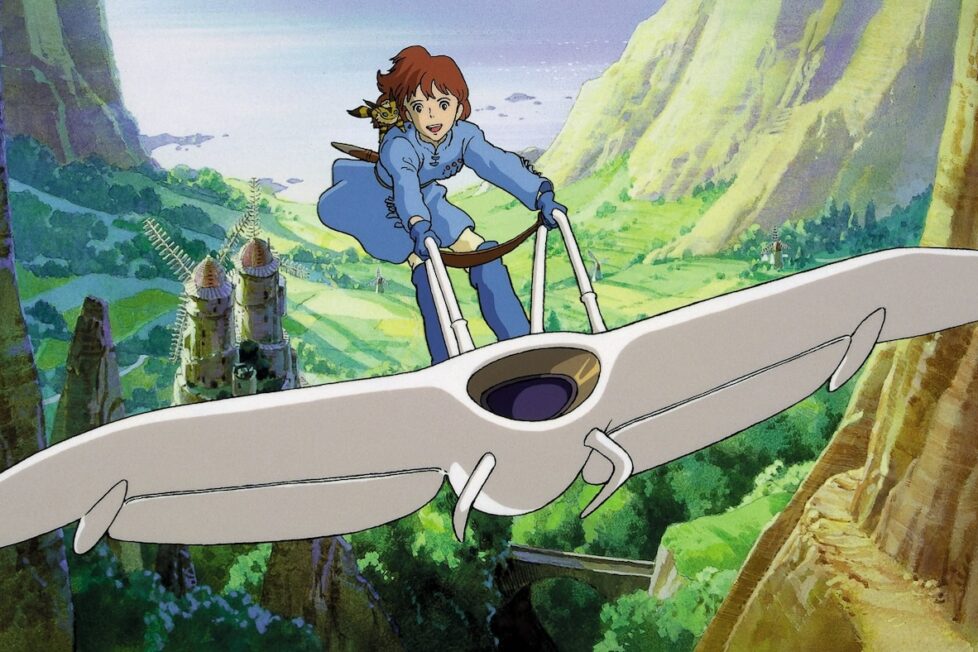

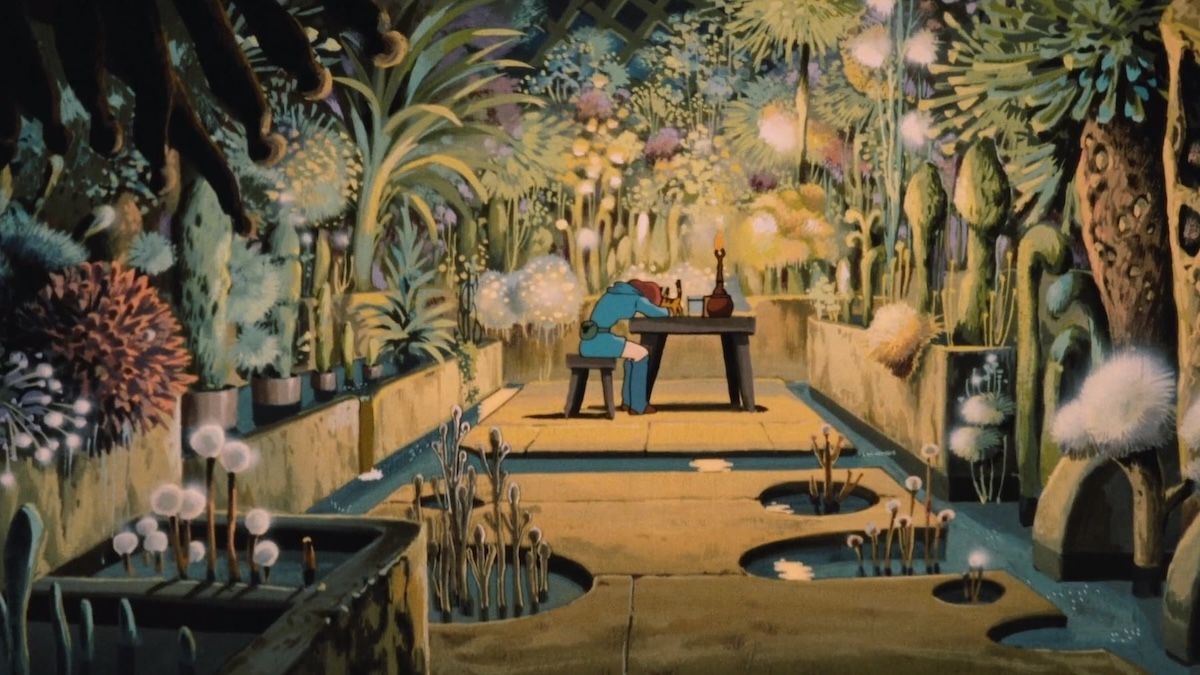

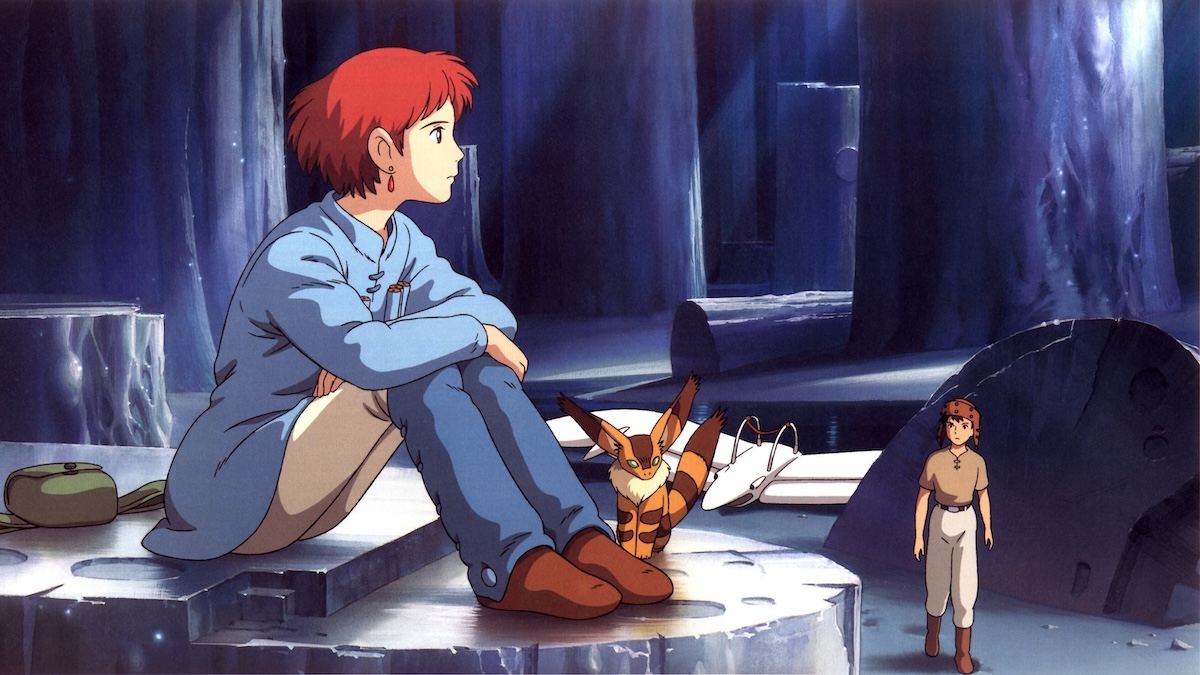

The Earth has fallen into a psychedelic state of devastation, characterised by a steampunk aesthetic. Airships bristling with devastating weaponry are adept at taking down their human foes, but are useless against the giant storm clouds crackling with lightning and buffeted by extreme winds. The weather conditions, however, pale in comparison to what lurks beneath the canopy of the toxic jungle: sprawling mushrooms, man-sized insects, and giant centipedes that soar through the poisonous air. It’s a colourful phantasmagoria, occasionally punctuated by a groovy, funky soundtrack.

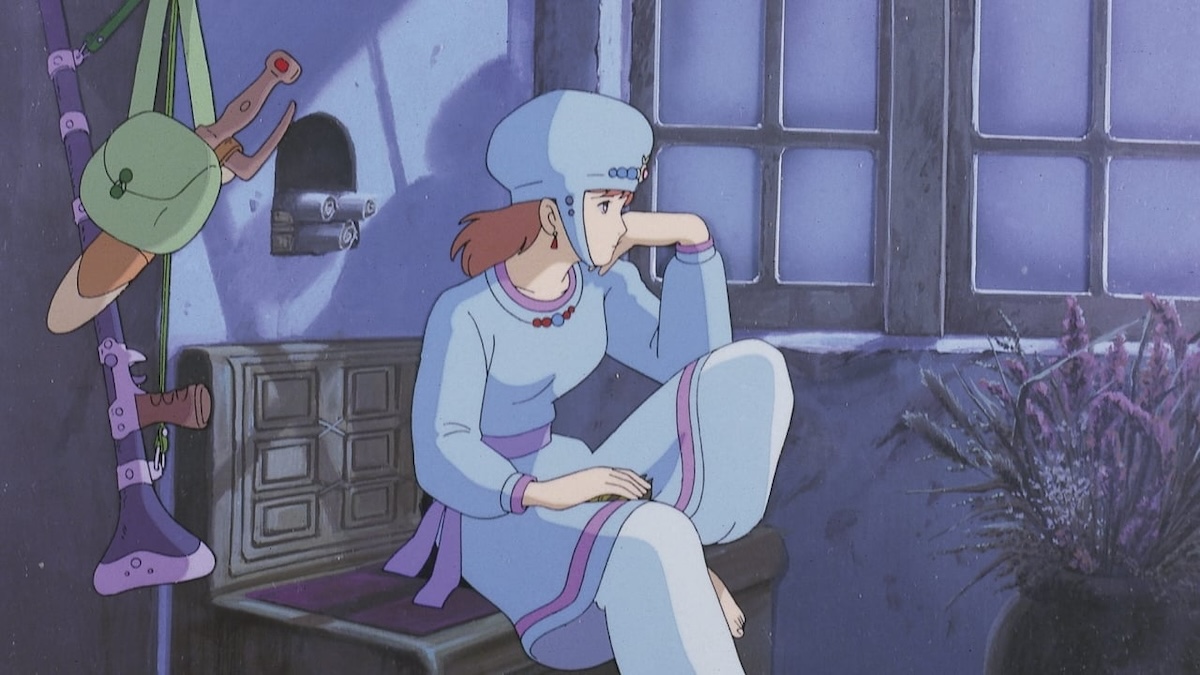

The animation style is also noticeably less polished than some of Studio Ghibli’s later works. It isn’t as clean-cut and instead possesses the same fluid texture as older, classic animation films. The animation team creates beautiful, immaculate transitions that enable the story to flow unimpeded, becoming akin to a moving painting. In short, the art design and everything visual about the film are absolutely phenomenal.

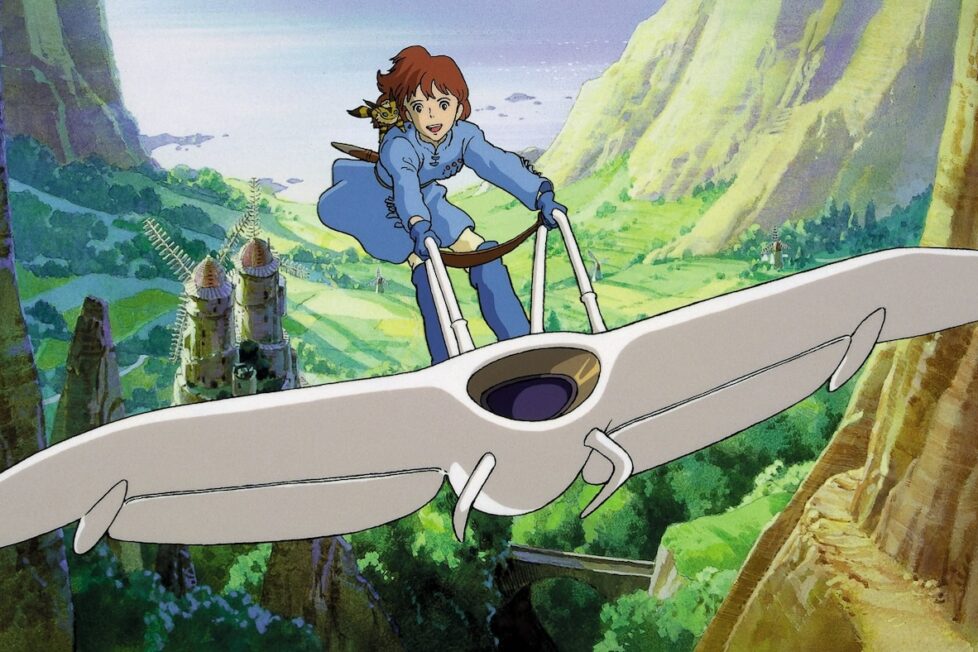

Of course, all this would be nothing without a compelling protagonist at the centre of our narrative. Fortunately, Nausicaä is far more than just compelling. She’s a stoic heroine, capable of remaining calm under pressure and in the face of tragic loss. However, she is also deeply emotional, which is arguably her greatest attribute. Her overwhelming capacity for compassion and empathy allows her to connect with the natural world. It also enables her to inspire the people of her Valley to follow her, despite the adversity they all must face.

Hayao Miyazaki demonstrates Nausicaä’s great character through breathtaking moments of bravery and sacrifice. As Nausicaä and her men glide through the toxic jungle, she takes off her mask to get the attention of her panicking subordinates. Here, we see Nausicaä as a charismatic leader who’s shrewd, wise, and daring, especially when compared to her slightly oafish male counterparts. Nausicaä embodies the archetypes of the huntress, the queen, and the mother in equal measure: she’s autonomous, focused, commanding, and, above all, nurturing. Nausicaä never desires to kill, with her overriding sense of humanity providing the greatest insight into the film’s themes of love, forgiveness, and understanding.

Miyazaki also uses other archetypes throughout the story to transform his film into a modern-day folktale. One example is Oh-Baba (which translates to “great old woman” in Japanese), who embodies the old, wise sage archetype. Additionally, Lord Yupa represents the battle-hardened, roaming warrior, a reimagining of the old rōnin character that made Akira Kurosawa’s films such global successes.

Perhaps the greatest demonstration of character in Miyazaki’s films is that the villains never become cartoonish or excessively malevolent. Instead, these warring, self-interested antagonists appear to be misled by their desires, suggesting they are not inherently evil. As David R. Loy and Linda Goodhew note in their essay The Dharma of Hayao Miyazaki: Revenge vs. Compassion in Nausicaä and Mononoke, the villainy portrayed in these stories reflects the Buddhist roots of evil—namely greed, ill-will, and delusion.

In Nausicaä, the terror felt by neighbouring factions inspires pre-emptive attacks, which only cause further destruction to the world they all share. The survivors in this post-apocalyptic world also fear the toxic jungle, which devours remaining resources, exponentially increasing scarcity. This dynamic is eerily similar to contemporary global politics, but that’s what Miyazaki does best: hold a mirror up to society in startlingly imaginative ways.

Perhaps most commendable about Miyazaki’s films is their demonstration of a harmonious approach to conflict, one characterised primarily by empathy and pacifism. They showcase how simplistic dualities like good and evil are too reductive to grasp the true root of the problem, offering a more nuanced analysis of humanity’s less attractive tendencies.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind successfully incorporates all these ideas, symbols, and themes thanks to its masterfully crafted narrative structure. The film is based on Miyazaki’s own manga series, which accounts for the exceptional world-building. The most crucial elements of the story are adapted for the big screen, and while the director uses some rather incongruous voiceover and clunky exposition at the beginning, these are the only remnants of its adaptation from another storytelling medium, as well as the only real flaws in the entire film. In that respect, it’s entirely admissible.

Much like the rest of Miyazaki’s work, a pervasive feminism runs throughout, though never is it didactic. He masterfully subverts genre expectations, most notably by flipping an age-old prophecy on its head. When Oh-Baba expects a fierce warrior to save the world, she’s visibly surprised to discover that it is, in fact, Nausicaä. However, this isn’t clumsily forced into the narrative; instead, it aligns perfectly with the visual symbolism of Mother Earth as a benevolent force—-Nausicaä embodies the quintessential warrior of her time, with empathy being her greatest weapon.

Other themes, such as war and environmentalism, strike us particularly hard when watched today. We’re left feeling saddened when Nausicaä asks, with such dumbfounded and melancholic intonation, “Who could have polluted the entire Earth?” This is especially impactful because the answer is so obvious: only humankind could have committed such heinous crimes against nature.

Miyazaki explores the perplexing human tendency towards violence and destruction most fully in his films Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and The Wind Rises (2013), although it’s arguable he does so even more effectively here. Fearful and suspicious characters destroy the world through factionalism, with petty local disputes diverting attention from the more significant fight for the planet and, indeed, the survival of the entire species.

The imagining of a place so bereft of vegetation speaks to the fears of nuclear fallout at the time. Indeed, Japan was less than 40 years removed from what’s arguably the most traumatic event in human history: the atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. In this respect, the giant warrior that Princess Kushana raises from the dead to cause unfathomable destruction (which she argues is for the sake of the planet) is symbolic of the nuclear anxiety that infused the late-20th-century.

Tellingly, the giant warrior melts and falls apart. Why? “The Earth knows it’s wrong for us to survive if we have to depend on a monster like that,” Oh-Baba elucidates. Poignantly, we discover that true power doesn’t exist in the capacity for violence, but in our capacity to heal and forgive. The tendrils of the Ohmu that envelop Nausicaa feel her pain, healing her in the process: it’s a stunning metaphor for the power of human compassion and the restorative potential of nature.

Miyazaki has made a handful of perfect films, an achievement few directors can claim. Spirited Away (2001) remains his finest work and, in my opinion, is likely the best animated film ever made. Princess Mononoke (1997) could also be considered flawless, featuring a plot remarkably similar to this 1984 gem. However, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is arguably his second-best film, despite being one of his most unsung.

As a nascent tree takes root, we see how a return to flourishing is possible when heroes stand up for what’s good in the world. Miyazaki’s story becomes a myth, imaginatively depicting how we all rely both on nature and each other. It shows how true strength lies in the fostering of life, not its destruction, and that the most formidable force in the world is love, in all its various forms.

JAPAN | 1984 | 117 MINUTES • 95 MINUTES (USA EDIT) | 1.75:1 (ORIGINAL) • 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE • ENGLISH (DUBBED)

director: Hayao Miyazaki.

writer: Hayao Miyazaki (based on his own manga series).

voices: Sumi Shimamoto, Gorō Naya, Yōji Matsuda & Yoshiko Sakakibara (Japanese Original) • Susan Davis, Hal Smith, Cam Clarke, Linda Gary (English Original) • Alison Lohman, Patrick Stewart, Shia LaBeouf & Uma Thurman (English ‘Disney’ Dub).