EUREKA (2000)

The survivors of a murderous bus hijacking come together and take a road trip to attempt to overcome their damaged selves, while a serial killer's on the loose...

The survivors of a murderous bus hijacking come together and take a road trip to attempt to overcome their damaged selves, while a serial killer's on the loose...

If it hadn’t been for Letterboxd’s list of its 250 highest-rated narrative films, it might have been years or decades until I learned of Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka. This is easily the most popular movie in the Japanese director’s filmography, though is still obscure enough to ensure that only ardent film fans will have come across any reference to it. Finding a copy of the movie is a more difficult task, but even then there are roadblocks, with Eureka’s DVD release by Artificial Eye failing to capture the unique colour scheme intended with its sepia tone.

In many ways, the film’s obscurity is its saving grace. A three-and-a-half hour Japanese drama meditating on the aftermath of a senseless act of violence is a tough sell for most film fans, such that it’s practically a guarantee that only those who enjoy arthouse, experimental, or slow-moving cinema will give this a shot. If the general public were to take a chance on Eureka, its appraisal on sites like Letterboxd would swiftly plummet, given that this is a taxing and draining work that seriously tests one’s patience.

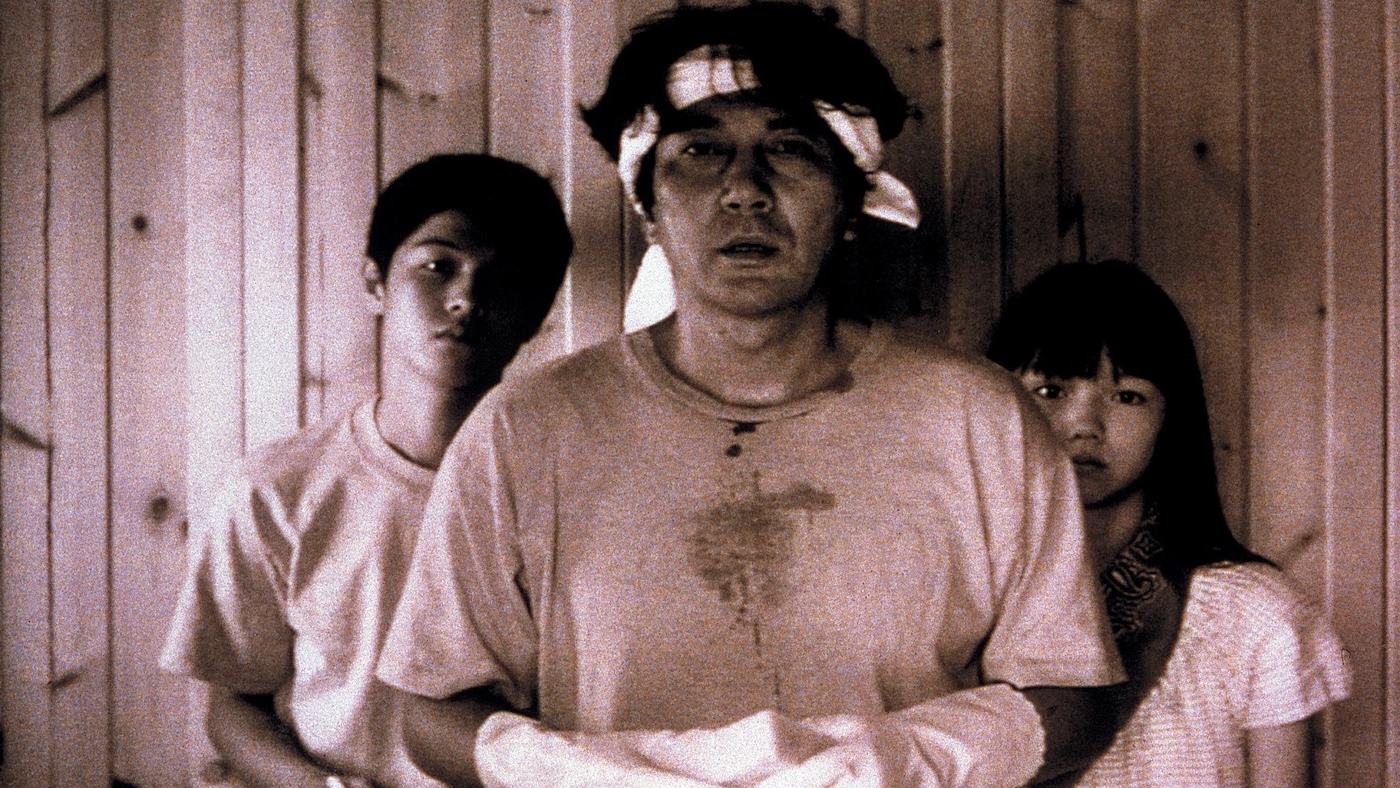

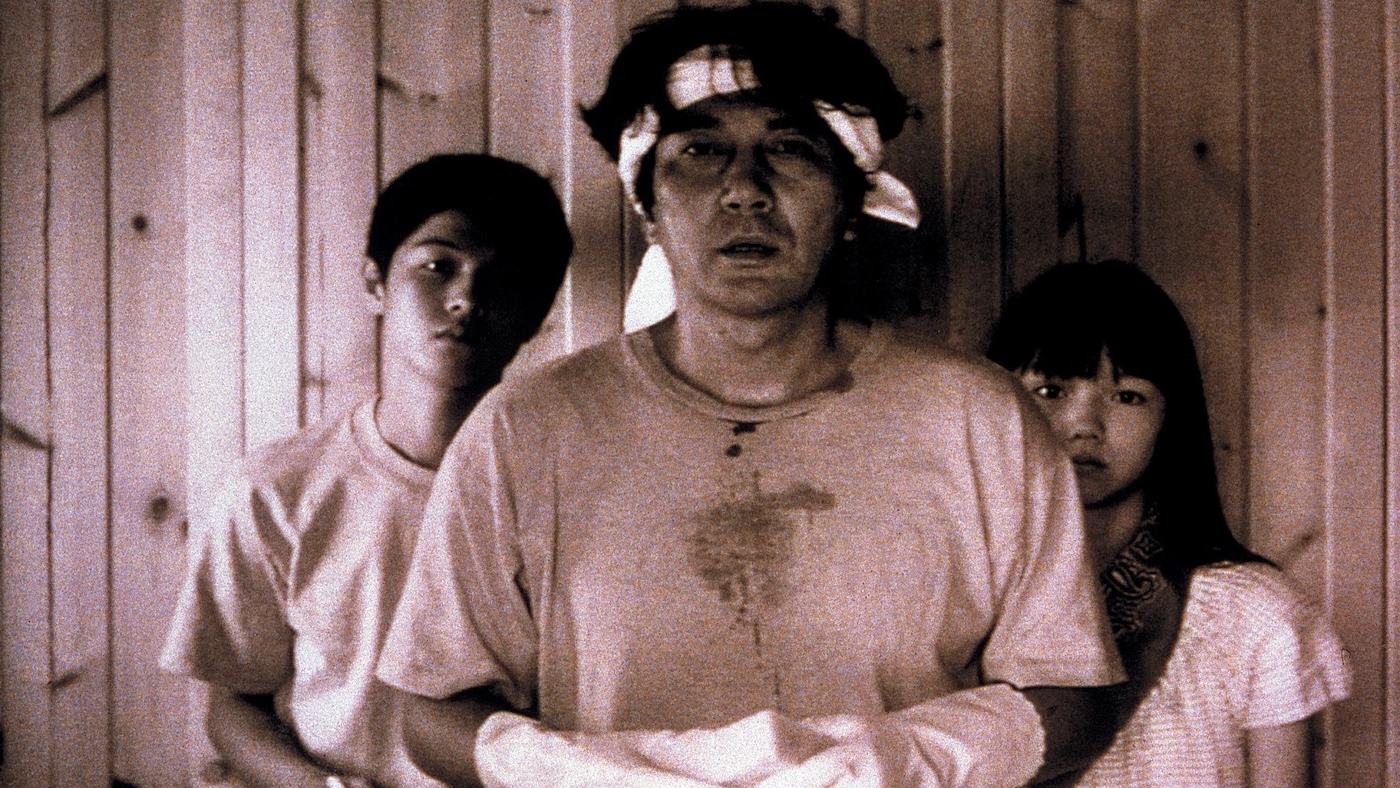

It also fails to live up to its adoring user reviews, which laud Aoyama’s ability to deliver a harrowing yet hopeful exploration of grief and learning to live with its presence. One doesn’t have to look far to find labels like ‘transcendent’ being used to convey the depth of this cinematic experience, which follows three survivors of a bus carjacking committed by a deranged gunman: bus driver Makoto Sawai (Koji Yakusho), and teenage brother and sister Naoki (Masaru Miyazaki) and Kozue Tamura (Aoi Miyazaki).

It’s always unwelcome to be let down by a film, regardless of one’s expectations for it, but it’s particularly disappointing when it’s something you’d been desperate to see before viewing. Eureka has its moments of beauty, and while the common colour grading of DVD copies available to viewers in the Western World is severely lacking in this regard, even that is not enough to stem some of the powerful imagery present. But it’s the story that lags severely, with a runtime so egregiously bloated that roughly 90 minutes could be shaved from Eureka and nothing of value would be lost.

For some viewers, a three-hour-plus film that’s both epic and a delicate tone poem sounds like a form of punishment rather than entertainment. Though it’s short-sighted to make such proclamations, in this particular case, it rings true. There’s a tangible sense of loss that perforates the surface of this film and its protagonists’ tortured states of mind, and Aoyama does well to recognise that silence is a powerful tool to convey this desolate alienation.

But wading through scene after scene with nothing meaningful binding them together, and no momentum present whatsoever, has the effect of turning what could have been a depressing tragedy into a depressingly flat experience. A vacant stare or a forlorn expression might as well be one and the same in Eureka, as while Aoyama never suffers with regards to technical proficiency, emotions are gradually compressed into static pieces of information and imagery, instead of being explored with the depth that astute characterisation or a moving story can provide.

Speaking of which, the twins’ empty expressions and refusal to speak set up instances of morbid comedy, where audiences are pushed away from focusing on despair and into that unemotional realm that registers a sad look as a temporary expression of upset, and not a conveyance of loss within the person wearing it. That instinctive response certainly isn’t helped by sequences that possess zero innately interesting qualities, and instead exist as a way of padding out the emptiness of these characters’ lives, a creative choice that will either prove completely baffling or profoundly meaningful to viewers, with little to no room for a middle ground.

What has captivated this film’s admirers as an astute study of grief instead comes across as a half-formed script executed by a director working on autopilot, filming an allotted number of scenes without any care put into whether or not they should make it into the final cut.

Eureka’s synopsis sounds fascinating: “In rural Japan, the survivors of a tragedy converge and attempt to overcome their damaged selves, all while a serial killer is on the loose.” It becomes significantly more underwhelming when you realise the main way they overcome their loss is by embarking on a bus journey throughout the island that they live on, which doesn’t begin until two hours of this laborious film have passed. Even then, the slow-moving arc of this narrative keeps feeling like a test of one’s patience.

After a strong opening scene that sets up Eureka’s slow pacing while delivering a tense showdown between the killer and his hostages, the film quickly loses—and never regains—a compelling narrative focus. Its goals are always admirable, but that does nothing to justify its many unnecessary or overlong sequences. A moment of silence that should be extended for two minutes or so will be stretched to double that length for no good reason, while many plot points which occur after Eureka’s inciting incident undercut its meditation on the effects of a random act of violence.

When these characters should be left to try to cope with this incident, they are instead propelled down a rabbit hole of abandonment, suicide, and murder, with another deranged murderer on the scene, this time one who is at large on their island. Even these grisly occurrences aren’t very interesting to follow given this film’s torturous pacing, but the more damning aspect of these narrative pit-stops is that they take away from the film’s exploration of loss and its impact.

Eureka strains at being contemplative and ends up as languid, where its commitment to a unique storytelling style is simultaneously the film’s most admirable and aggravating quality. Its score, which is consistently beautiful, goes a long way towards conveying the pain and hope lingering within these characters’ grand journey, which they are unable to articulate through dialogue, while Yakusho’s leading performance further cements him as one of Japan’s finest performers.

I can’t say I was nearly as impressed by the two teen performers, who offer middling portrayals of muted emotions (helping to mask what appears to be their limited range), though it’s impressive that a real-life brother and sister duo took on these roles. But these positive qualities only go so far in livening up this flat, inert cinematic experience, whose occasional glimmers of beauty are so few and far between that Eureka is best summed up as a punishing slog.

JAPAN • FRANCE | 2000 | 218 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

writer & director: Shinji Aoyama.

starring: Kōji Yakusho, Aoi Miyazaki, Masaru Miyazaki, Yoichiro Saito, Sayuri Kokushō, Ken Mitsuishi, Gō Rijū & Yutaka Matsushige.