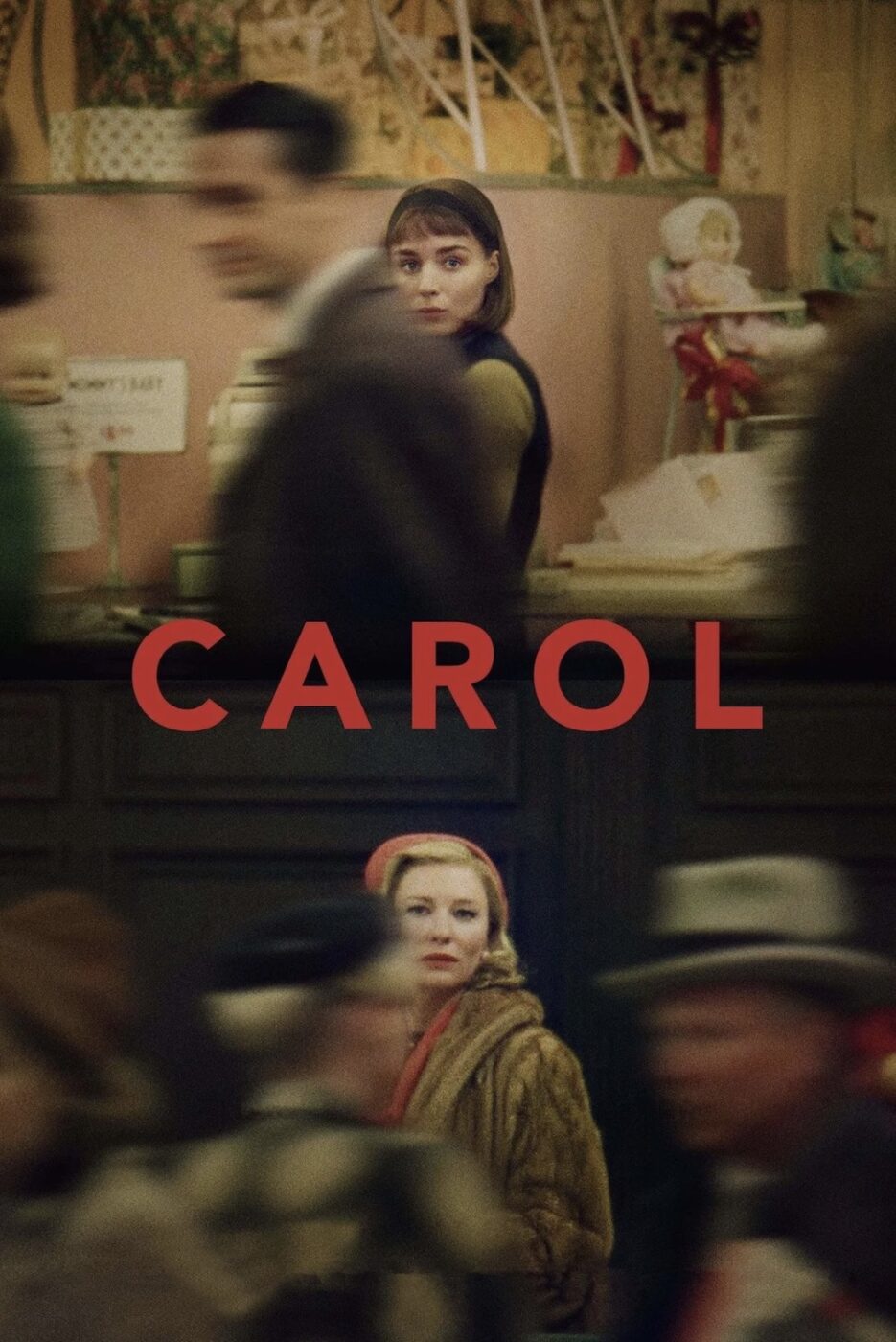

CAROL (2015)

An aspiring photographer develops an intimate relationship with an older woman in 1950s New York.

An aspiring photographer develops an intimate relationship with an older woman in 1950s New York.

Few writer-directors are as well-equipped at dealing with the realms of love and repression as keenly as Todd Haynes. Whether it’s the stifling atmosphere of everyday suburbia or deceptive cults in his sophomore feature Safe (1995), or a heart-breaking look at the limitations of freedom to love in the Douglas Sirk-inspired Far From Heaven (2002), this is Haynes’ bread and butter. No other director could be more suited to a mid-20th-century love affair between two women. Haynes is just as evocative at conveying the subtle power of a look as he is in quieter versions of despair that romantic tragedies like Brief Encounter (1945) draw out in spades.

Carol, based on Patricia’s Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, is a coming-of-age story, yet it hardly feels like one when Haynes and screenwriter Phylis Nagy comfortably sidestep the genre’s many clichés (an especially difficult task given how formulaic many stories set in 1950s America already are, replete with wooden dialogue and walking, talking archetypes). Aspiring photographer and shop assistant Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) is only just beginning to blossom in her hobby and desired profession. She also has no personal experience or frame of reference for romantic love with a woman when she encounters the enigmatic, much older Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett), who Therese meets by chance at her workplace. Silent glances and open stares soon become a recurring facet in this film, and for good reason, since Carol’s near-perfect gaydar has allowed her to spot interest from Therese instantly, despite this young woman not seeming confident she was even aware of such a feeling.

With a framing device ripped straight from Brief Encounter (but which is moving enough to pass as a respectable homage), we are greeted with a sombre conversation between Therese and Carol at the film’s outset, soon interrupted by a misunderstanding onlooker, who breaks up the interaction with no recognition of its importance. Sometime later, Therese silently studies passersby as she and some work colleagues drive to a function together. Looking outside the window, she appears to take great interest in the groups of laughing, playing children, or a charming couple preparing for their evening out together. Unbeknownst to us now, it will later become clear that this is when Therese has developed an interest in people as subject matter for her photography, just as she’s developed confidence regarding her abilities and insight into what makes a great picture.

This creates a dual function for the tragedy that lies before her, with the promise of openly raising children or being in a loving relationship presumably cut off from Therese if she pursues romance with Carol (or any other woman). But this reflective scene also highlights the importance of movies like this, where Therese must reckon with the fact that the love she shares with Carol can never be featured and spotlighted by her photography. Her societal upbringing ensures that one of her passions is prohibited in documenting the other, lest those images be made public and lead to her undoing. It’s no wonder that at the start of Carol (the chronological beginning) Therese is hesitant to articulate her emotions and seems ill-equipped to reckon with them. She can be herself behind the camera as the watchful, insightful observer, but none of that will bring her closer to the passion she experiences with Carol, since it can never be expressed publicly.

Although Carol, with its dedication to documenting even the minutiae of its period piece setting (with an appropriately grainy look to boot), seems poised to be an exercise in repression, it gradually blossoms into a delicate romance. Whether it’s being withered away by the fear of being outed or this pair’s very different, and constantly changing, lives, the spark at the heart of this movie often wavers. This beautiful, hopeful tale of self-discovery is reticent to put labels on these characters, especially Therese, who could just as easily be a lesbian as bisexual. It’s not so much that we shouldn’t be privy to this information (though there’s something satisfyingly tender and empathetic about this movie’s noncommittal attitude to such terms), but that Therese herself has never been offered the tools to carve out this new identity for herself. It’s a path she must take alone, with no outside examples to give her strength.

Haynes and Nagy keenly recognise that there’s no other way to depict this love affair, and blossoming self-discovery, than through restraint. The pair replace lengthy backstories, self-defeating stereotypes, and an overemphasis on the tragedy of the times or the comparatively optimistic developments today with a story that recognises the kind of beauty and romance that is unappreciable to the unattuned eye. It’s no wonder that the man who interrupts Carol and Therese’s conversation fails to recognise its gravity; he has never had to live a life of concealment, has never had to reckon with the value of a brief smile or silent look of longing with someone you can never love openly. This film’s sumptuous and delicate qualities may stand out the most, but it’s Carol’s maturity that proves its defining element.

Some of the film’s casting choices are so fortuitous that they seem as if they were destined to be. Cate Blanchett as Carol appears elegant and refined even in moments of crisis, a human being with real strife and inner turmoil who can also exist as an avatar for all that Therese can’t imagine herself as. As she reckons with while watching passersby, the life that Therese imagines with Carol has never been reflected back at her. But with this elegant yet forthright older woman in her presence, this protagonist can finally imagine a new way of living.

Yet one can also just as easily imagine what is so intoxicating for Carol in her new lover. Mara’s distinctive looks have never been so aptly put to use throughout her career than here, with her wide-eyed optimism, a smile that lights up her entire face, and looks of intense concentration that imply a level of maturity that covers up her inexperience in this realm. When the pair are beholding one another, real magic unfolds on screen. Silent communication is the name of the game here, and Mara and Blanchett pull it off masterfully.

But even the minor parts are perfectly cast. Sarah Paulson is ideal as the lesbian best friend character, a rather helpful plot driver who the film doesn’t afford the pretence of real agency. It’s the sort of bit-part that should feel cliché and throwaway, but Paulson turns in a great performance nonetheless. Her silent pity towards the grief-ravaged Therese when she and Carol experience a falling out is surprisingly touching. In Carol, the casting isn’t just pitch-perfect because of the calibre of the performers involved, but in how they look. It’s a continually curious discovery to come across actors and actresses who look completely differently in media to how they must in reality.

Jake Lacy, who portrays Richard, Therese’s boyfriend for a time, would surely be an attractive figure if one were to come across him in real life, but there’s something about his smarmy smile and petulant, entitled expressions of discontent that makes him well suited to dim and unlikable characters. Kyle Chandler, meanwhile, works very well as a cold and distant husband to Carol, who, despite his apparent aloofness, is very controlling when he feels the compulsion to be.

As for this love story, while there are many touching moments along the way and Haynes’ direction is continually masterful, its dedication to gentleness doesn’t always feel like the correct posture. While Luca Guadagnino’s romance between an older and younger character in Queer (2024) is so sweaty and desperate that one feels clammy and lonely just watching it, Carol affects a more distant pose, resting on its delicate laurels without a much-needed break from them.

Seeing these characters’ hearts go aflutter in each other’s presence is a delightful treat, but a more forceful edge to this film’s sensuality would have been an even more appreciable tonic to balance out its refined pleasures. Francis Lee’s Ammonite (2020), which presents a lesbian love story in the 19th-century, contrasts its ice-cold weather conditions, dreary lifestyles, repression, and thankless outdoor work with the impassioned sex scenes and non-physical intimacy between its unlikely lovers. But Carol and Therese, in spite of their differences in personality and stations in life, fit like a puzzle piece.

They’re too in tune with one another on an interpersonal level to unlock something desperate in their romance or lovemaking; instead, the film’s lone sex scene is treated with the same degree of gentleness as the rest of the film. Unlike some garish depictions of lesbian romance in media, Haynes and Nagy seek to move in far more refined, tasteful territory, but that sometimes comes across as a respectful overcorrection instead of what would best serve the film’s dramatic core. Carol works wonders with its limitations, imposing its strong emotions masterfully on something as simple as a glance, even if those self-imposed limitations don’t always benefit this experience.

UK • FRANCE • AUSTRALIA • USA | 2015 | 118 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Todd Haynes.

writer: Phyllis Nagy (based on the book ‘The Price of Salt’ by Patricia Highsmith).

starring: Rooney Mara, Cate Blanchett, Kyle Chandler, Sarah Paulson, Jake Lacy, John Magaro, Cory Michael Smith & Carrie Brownstein.